This is the third Insights article in our data disaggregation series, along with articles on Minnesota’s Black and Asian communities.

In the U.S. Census, “Hispanic” and “Latino” are used interchangeably, but these two terms have different meanings. “Hispanic” refers to individuals who speak Spanish or come from a Spanish-speaking country (like Spain), whereas “Latino” refers to those who come from Latin America. People with Hispanic or Latino ethnicity can also identify as any race, which can include a wide range of ancestries, birthplaces, and cultural identities. For example, a person can be Black and Hispanic or Latino. Grouping people who speak the same language, or who have ancestry from similar parts of the world, is common practice in data collection and analysis. However, when we combine groups in this way, we can also miss nuances in the data that help us understand the quality of life for distinct cultural groups. This article highlights the importance of data disaggregation in understanding the varying lived experiences of Hispanic and Latino Minnesotans.

Minnesota’s Hispanic and Latino communities are diverse

Minnesota is home to more than 370,000 Hispanic or Latino residents or about 7% of our total population. After Minnesota’s White and Black communities, Hispanic and Latino Minnesotans make up the third largest population group. While Mexican Minnesotans make up more than two-thirds of this group, it also includes people from other heritages, backgrounds, and ancestries, including Puerto Rican, Ecuadorian, Salvadorian, Guatemalan, Cuban, and Colombian.

NOTE: We use total Hispanic population numbers of 360,000 for the chart above to correspond to the 2018-2022 select cultural community numbers.

Experiences, strengths, challenges, and needs vary by community, which is why disaggregating populations beyond broad census-level race groups is so important.

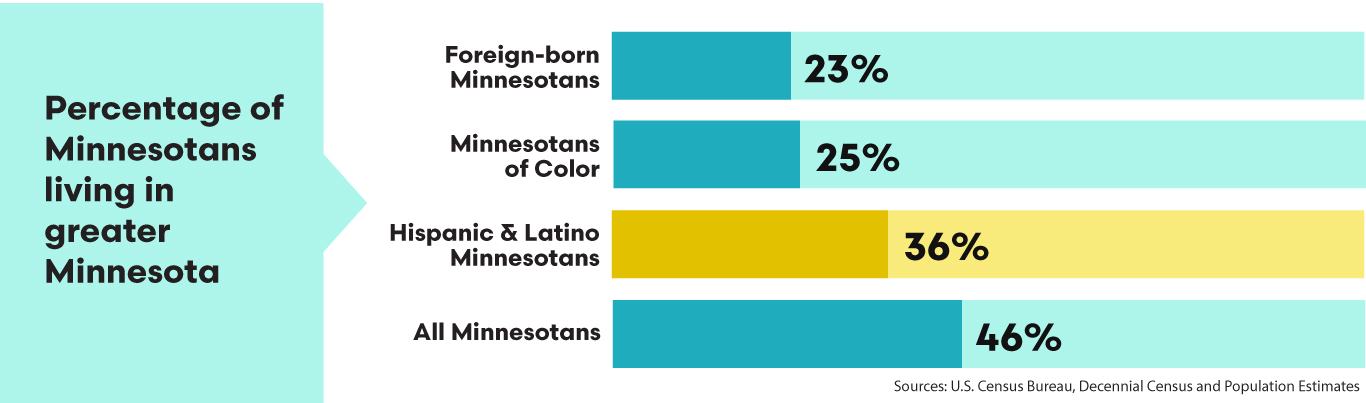

Unlike other racial groups, there is a greater share of Hispanic and Latino Minnesotans living in greater Minnesota

In Minnesota, nearly 25% of people of color and 23% of foreign-born residents live in greater Minnesota. While the Twin Cities metro area is attractive for many— whether that is to be close to established cultural communities, to pursue educational and employment opportunities, or for access to social services or public benefits—our data suggest that this shows up differently in Hispanic and Latino communities. Nearly a third of Hispanic and Latino Minnesotans live in greater Minnesota and are contributing to the workforce and economies outside of the metro. An example of this is Nobles County, where 30% of residents are of Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. Nearly half of Guatemalan Minnesotans (48%), and 40% of Mexican Minnesotans live outside of the Twin Cities metro area.

Hispanic and Latino Minnesotans are an integral part of Minnesota’s talented workforce

In general, employment among Hispanic and Latino communities is high, with proportions of adults working ranging from 72% to 80%, close to Minnesota’s overall employment level of 79%.

While high rates of employment among working-age Hispanic and Latino Minnesotans are contributing to Minnesota’s vibrant workforce and economy, stark differences in quality-of-life outcomes show that there is still significant work to do when it comes to addressing inequities. We know this holds even more true for unique cultural communities.

Quality-of-life outcomes tend to be better among cultural communities with higher educational attainment

While the share of Hispanic and Latino Minnesotans with a high school degree is 73%, educational attainment varies across select cultural communities. For example, greater shares of Cuban, Colombian, and Puerto Rican adults have a high school degree -- 12 to 20 percentage points higher than among all Hispanic and Latino Minnesotans.

We also see greater shares of adults with a bachelor's degree or higher in these cultural communities. More than half of Colombian Minnesotans (53%), 38% of Puerto Rican Minnesotans, and 36% of Cuban Minnesotans have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

In cultural communities with higher levels of educational attainment, we also tend to see higher median incomes, home ownership rates, and potential wealth stability through housing.

For some communities, limited generational wealth-building impacts quality of life

Median household income among Hispanic-headed households is $63,400, but this varies widely across select cultural communities. Where Salvadoran-headed households make nearly $17,000 more than the average Hispanic- or Latino-headed household, Guatemalan-headed households' median income is about $8,000 below the average.

Across Hispanic and Latino cultural communities, Guatemalan Minnesotans' poverty rate is also one of the highest rates of poverty.

Home ownership is one way cultural communities can build generational wealth.

Home ownership rates are lowest among cultural communities with lower educational attainment, lower household income, and higher rates of poverty. Whereas half of all Hispanic- or Latino-headed households own their own homes (49%), smaller shares of Guatemalan- and Puerto Rican-headed households own their own homes (45% and 35%, respectively).

There are also disparities between cultural groups in housing cost burden, or households paying 30% or more of their income for housing. About 35% of Hispanic and Latino Minnesotans are housing cost-burdened. This is even higher for Ecuadorian, Puerto Rican, Salvadoran, and Guatemalan households.

Minnesota’s Hispanic community is not a monolith

As a combined group, Hispanic and Latino Minnesotans are the third largest racial/ethnic group in Minnesota. Data disaggregated by cultural community show us that each cultural group has unique stories, experiences, and quality of life outcomes. It’s important to understand that identities are social constructs, and existing data is only able to shed light on portions of the entire story.

No one data source—on its own—can tell the full story. Data disaggregation is a step in the right direction and we have pulled together multiple self-reported characteristics—ancestry, ethnic group, birthplace, parents’ characteristics—to provide a more nuanced understanding of unique cultural communities. But we are talking about complex social issues that not only require information from multiple sources, but also rely on community wisdom to make meaning and identify necessary actions.

Additional resources

- Data profile for all Hispanic and Latino Minnesotans

- Data profiles for Minnesota’s detailed cultural communities

- Minnesota’s Latinos in numbers by Rodolfo Gutierrez and Daisy Richmond

- Minnesota’s Hispanic population: 5 interesting trends

- Race data disaggregation: What does it mean? Why does it matter? by Nicole MartinRogers

- “Why aren’t I represented on Compass?” by Anne Li

More about data disaggregation

In response for the need for better visibility and representation, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) has revised data collection standards in regards to race and ethnicity (read our Insights article on the revised standards). The data presented in this article reflects data from two separate questions asking about race and ethnicity, leaving those that identify with Hispanic/Latino ethnicity to identify themselves with limited race options – American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Hispanic or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and/or White. The revised data collection standards will now include Hispanic or Latino as one of the race categories. With these revision announced earlier this year, federal agencies are expected to fully comply with new standards by March 2029.

To identify cultural communities, Census responders are able to self-identify when filling out forms and are able to self-describe their origins. For example, on the American Community Survey, Hispanic or Latino responders are presented with instructions to print their origins. The Census Bureau’s code list includes more than 30 Hispanic or Latino subgroups.

Additional items further on in the survey ask about place of birth and ancestry or ethnic origin. For estimates in this article, all of these characteristics—in addition to parents’ characteristics for children under 18—were factored into identifying individuals from unique cultural communities.