Shortly before graduation, my high school physics class held a bridge-building contest. My partner and I measured miniature wooden “beams,” made precise incisions, and applied our best understanding of the physics of tension and balance. We even added decorative curlicues.

It paid off! The day of the contest, the bridge held more than two thousand times its own weight. What’s more, we won second place for “Most Creative Bridge.” (This is similar, but much preferable, to receiving the Monopoly card for “Second Prize in a Beauty Contest.”)

While my partner and I were proud that the bridge proved both structurally and aesthetically strong, the project provided other benefits: We learned to research the operations behind everyday objects, gained confidence in our ability to understand complex ideas, and applied the knowledge in a practical way.

Those skills have proved invaluable. Beyond suggesting that I could have a place in a field such as engineering, should I choose to pursue it, I have confidence to explore complex questions, develop responses, and create a structure to put them into action.

Confidence and the ability to apply knowledge in useful ways are only two of the possible results of a strong STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math) curriculum. In fact, investment in STEM can bring myriad positive results at the personal level and a broader, statewide scale.

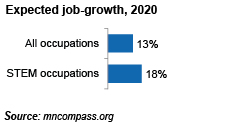

One example is job growth and the economy. Job growth in STEM is expected to outpace overall growth in Minnesota from 2010 to 2020 (18% growth in STEM compared to 13% overall). These jobs, comprising a variety of skill sets, may contribute to Minnesota’s strength and prosperity.

However, although STEM is one of Minnesota’s faster-growing fields, it is affected by patterns of underrepresentation, underachievement, and missed opportunities, including for women.

Gender disparities in STEM workforce and education

A recent white paper from Wilder Research, Education and Workforce Disparities: Gender – A cradle to career perspective, points out disparities in the ability and participation of workers to fill jobs in the STEM field. It also presents ways to address the gender gap.

The paper helped me understand how the supports I have received moved my interest in STEM to ability, and, finally, to possibility. Mentorship, informal supports, high quality educational curricula, and the presence of role models engaged my imagination and helped counter stereotypes that women are inherently less able in STEM.

On a broader scale, the paper shows how those supports—formal and informal, small-scale and systemic—can play a role in Minnesota’s prosperity and the quality of life that all residents should enjoy.

The implications of a workforce equipped to fill higher-level positions include greater wealth, economic security, and investment in the things that make our community strong: sense of place, education, and infrastructure, to name a few. However, there is a gap in our preparation to fill these positions.

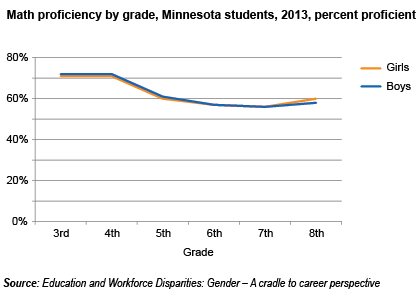

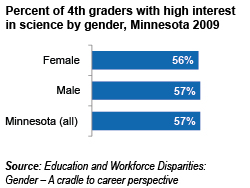

Addressing gender equity may help to make up the difference. For example, the STEM occupations most likely to face worker shortages in Minnesota are male-dominated. Data indicate that girls and boys in Minnesota are about equally interested in STEM during elementary and middle school. Girls’ and boys’ proficiency in math is similar during that time. However, boys are more likely to be college-ready in math and science than girls, according to ACT results. Men show greater interest in STEM occupations at the college level. Would shoring up the skills of female students in STEM help address the worker shortage?

Building a strong cadre of workers to support Minnesota depends on how well we prepare and support students along the spectrum from cradle to career. But how early do the disparities appear? Several sources of data confirm that there is little difference in math proficiency between girls and boys in elementary and middle school. However, the story changes as students move toward high school and college. In 2013, 47 percent of eighth-grade boys in Minnesota met or exceeded grade-level standards in science. Only 40 percent of girls met or exceeded the same standards.

Step by step

There are ways we can take action to address disparities in women’s ability and participation in STEM. Coordinating informal education efforts along the educational continuum can ensure that students have ample opportunity to explore, ask questions, and develop STEM competency. Engaging girls in “hands-on” investigation can demonstrate that they do belong in STEM fields. Connections with STEM role models, coordination among informal education providers, and college or university STEM programs may help reduce the perception that women can’t succeed, make a difference, or earn a suitable salary in STEM fields.

Data from a national survey indicate that nearly identical proportions of Minnesota fourth-grade girls and boys have high interest in science. If we prepare students—and their teachers—to take advantage of interest in STEM, our workforce may be better equipped to fill jobs in coming years.

I believe we can find hope in the fact that solutions can be brought to bear on the problem years before we encounter the more severe consequences of a gender-based workforce gap. By exploring the state of STEM in Minnesota and taking effective action, we can build a bridge between today’s students and tomorrow’s strong workforce.

Learn more about this issue:

Education and Workforce Disparities: Gender – A cradle to career perspective is part of a series of white papers on disparities in STEM.

Join the conversation at #CompassSTEM

Related:

Sparking tweens and teens interest in STEM -- Lisa de la Cueva, Community Technology Empowerment Project

Building a pipeline of talent -- Marilee Grant, Boston Scientific community relations director

STEM in Minnesota: A research-based framework for action -- Caryn Mohr, research scientist, Wilder Research